Whose side are you on? Facebook thinks it knows best

The partisanship at play in the US elections, and no less at home post-Brexit and over a ideologically split Labour party, revives the debate over the way algorithms that personalise your online worldviews can close you off to outside points of view.

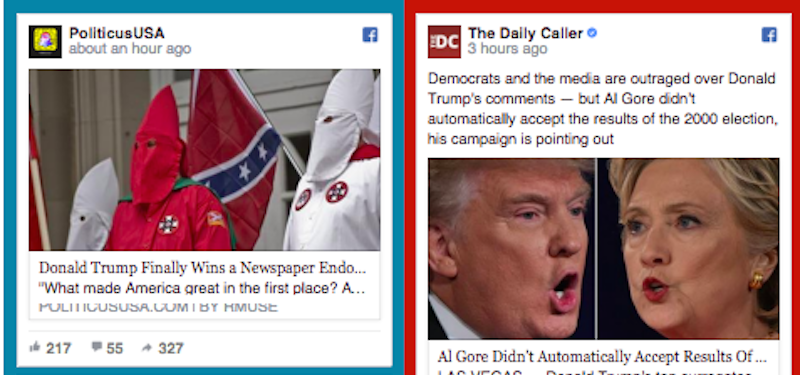

The Wall Street Journal’s Jon Keegan connected with Hacks/Hackers London this week to demonstrate Blue Feed, Red Feed, which visualises a Facebook news feed for two theoretical US users: one “very conservative,” one “very liberal.” The difference was striking. As Keegan told his London audience, whole swathes of sources were cut out of different news feeds by Facebook’s algorithm, which is set to bring news that reflects individual user interests, and those of their peers.

Technology analyst Eli Pariser famously called this the “filter bubble” – an echo chamber, with users seeing news aligned with their own political leanings, or worse reinforcing their prejudice with conspiracy theories or propaganda. But does Facebook have a responsibility to tweak its personalisation algorithm so that news feeds bears fewer holiday selfies and more news items that challenge its users’ political worldview and encourages democratic discourse? Keegan’s WSJ colleague Geoffrey Fowler suggests that Blue Feed, Red Feed might be the product Facebook needs, but never built: “a feed tuned to highlight opposing views. Once you take a detour to the other side, your own news looks different—we aren’t just missing information, we’re missing what our neighbours are dwelling on.”

If you are wise to the ways of Facebook, there are ways to try and counter its algorithm’s baleful influence. Facebook adds a “people also shared” link box to posts with related, but not necessarily critical opinions that might broaden your view. You can tweak preferences to prioritise sources that might take a different view to those you normally follow, if you know who they are. Using the ‘sad’ or ‘angry’ tags instead of the undiscriminating ‘like’ button, should have an eventual effect on the nature of your feed. How strong that effect is cannot be readily measured as Facebook strictly limits access to the raw data it collects.

As for Facebook itself, as so often with its management of obligation, it wavers between cautious acknowledgment of the issue to laboured avoidance. Keegan based his visualisation on data sources assigned to Facebook’s own study of the issue, Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook, by Eytan Bakshy, Solomon Messing & Lada Adamic, published in Science magazine.

The study claimed that almost 29% of hard news run by its newsfeeds cut across ideological lines. But its claim to “conclusively” establish that “individual choices (matter) more than algorithms” on Facebook was strongly contested. Filter bubbles were the user’s fault, the study said: “The power to expose oneself to perspectives from the other side in social media lies first and foremost with individuals.” The Facebook algorithm, it said, doesn’t create filter bubbles, but simply reflects our own tastes and commitments.

Social media theorist Nathan Jurgenson viewed this of the same politics and logic as “guns don’t kill people, people kill people,” the same fallacy that technologies are neutral, that they are “just tools”. “Facebook’s ideological push to dismiss the very real ways they structure what users see and do is the company attempting to simultaneously embrace control and evade responsibility.”

But the study sidestepped a potentially greater problem. The Facebook study essentially mapped which articles tend to get shared the most by different ideological groups. It wasn’t a measure of how partisan-biased the news article or news source was itself. The new problem is a rise in sites that successfully game the algorithm to promote content on Facebook that is at best partisan, at worst aggressively prejudiced or flat-out lie, but still gaining millions of ‘likes’ in the process.

It’s the work of political news and advocacy pages, writes the New York Times, made specifically for Facebook and “uniquely positioned and cleverly engineered to reach audiences exclusively in the context of the news feed”. Cumulatively, their audiences of tens of millions rival better-funded political media corporates giants like CNN or the NYT itself, “perhaps, the purest expression of Facebook’s design and of the incentives coded into its algorithm”.

This week a Buzzfeed special found that three big right-wing Facebook pages published false or misleading information 38% of the time during the period analysed, and three large left-wing pages did so in nearly 20% of posts. BuzzFeed drew a troubling conclusion: “The best way to attract and grow an audience for political content on the world’s biggest social network is to eschew factual reporting and instead play to partisan biases using false or misleading information that simply tells people what they want to hear.”

The traditional interpretation of the ‘free market of ideas’ that underpins freedom of expression in politics and online is that good, validated, honest opinion will win out against the malicious untruth. But the sheer proliferation of conspiracy laden or just plain false fringe content challenges this view.

Buzzfeed’s review of 1,000 posts from six ‘hyper-partisan’ political Facebook pages on both right and left found that the least accurate pages generated some of the highest numbers of shares, reactions, and comments — far more than the three large mainstream political news pages analysed for comparison. They judged 38% of all posts on three right-wing Facebook pages to be either a mixture of true and false or mostly false (19% of posts on three equally hyper-partisan pages on the left-wing were found to be the same).

Buzzfeed tracked Left-wing pages that claimed Putin’s online troll factory rigged online polls to give Donald Trump won his first candidate’s debate and that the Pope “called Fox News type journalism ‘terrorism’.” The Freedom Daily page, which has 1.3 million fans, had 23% of its posts to scored as ‘false’ and 23% more, a “mixture of true and false” information.

Conspiracy theories ranked highly. Buzzfeed cited right-wing pages that pushed a theory about a Hillary Clinton body double, and that Barack Obama went to the UN to tell Americans they needed to give up their freedoms to the “New World Government”. Worse, writes technologist Renee di Resta, “once people join a single conspiracy-minded group, they are algorithmically routed to a plethora of others”.

Rather than pulling users out of the rabbit hole, they get pushed further in. “We are long past merely partisan filter bubbles and well into the realm of siloed communities that experience their own reality and operate with their own facts.”

“Each algorithm contains a point of view on the world,” concludes Pariser in his own peer review of the Facebook research. “Arguably, that’s what an algorithm is: a theory of how part of the world should work, expressed in math or code. So while it’d be great to be able to understand them better from the outside, it’s important to see Facebook stepping into that conversation. The more we’re able to interrogate how these algorithms work and what effects they have, the more we’re able to shape our own information destinies.”